Table of Contents

While we are used to seeing a king, queen, president or prime minister on our modern day coins, the ancient Greeks would open a fist full of ancient Greek coins and see the deity most associated with their city, or “polis”. It was a commonly held belief of the Greeks that their day-to-day actions were carried out under the watchful eye of these deities, and with each city so tightly connected with the particular deity or god they worshiped, the images were more than depictions of their heroes, but were actual emblems of the cities (or “poleis”) themselves.

*This post may contain affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Church and state had no separation, and this fact is made vivid when studying ancient Greek coins. It is these pious, administrative depictions that help us identify ancient Greek coins and help distinguish one era or geographical location from another. These identifiers are very important in contemporary coin collecting as a “Metapontion” in place of a “Larisa” could mean a difference of thousands of dollars.

What Constitutes an Ancient Greek Coin?

Greek coinage consists of the non-Roman coins of the ancient world, roughly making up the geographical area between the Straits of Gibraltar and northwest India, beginning in the period around the 7th century BC to the dawn of the Roman era in the 1st century BC. If one takes into consideration the long history of mercantile exchanges made with any number of materials, including giant stones, wheat, or barley and precious metals, the production and widespread use of coined currency was a fairly late development.

Masters of Minute Sculpture

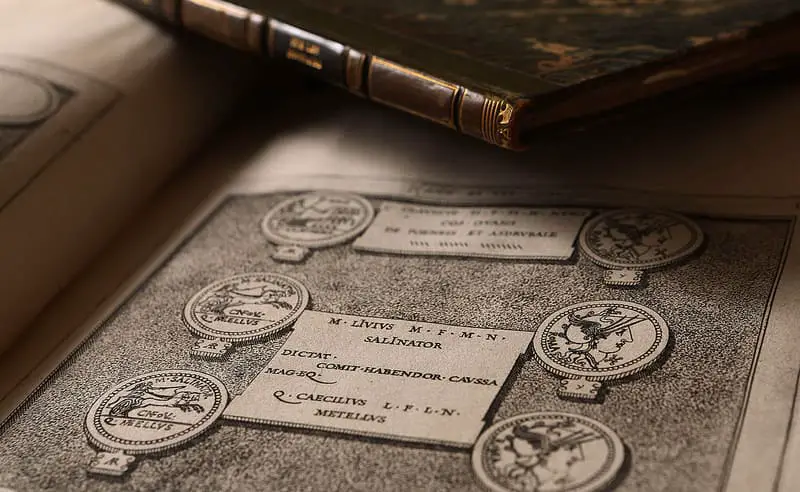

We all know that Greek sculpture is some of the most beautiful and skillfully crafted in all of history. Taking this skill to the smallest scale available, we find this craft and beauty in ancient Greek coins as well. In these tiny circles, some of them mere millimeters in diameter, the Greeks applied all the qualities of their sculpture, rendered visible in the subtleties and harmonies of human, animal, and object forms.

From their archaic origins, we can follow the art inherent to Greek coinage to the apex in the classical period and later, a snapshot of the Greek cultural decline. In the numismatic archival records of ancient Greece, one can see the political, cultural, economic, and commercial saga of the Greek world laid out in miniature.

The Benefits of Investing in Ancient Greek Coins

Investing in collectibles such as rare coins is a very good way to expand your portfolio and minimize your risk. Many people invest in the collectibles they have an interest in, whether it be contemporary art or old baseball cards, and with such a rich history associated with ancient Greek coins, it certainly satisfies a corner of this niche market.

Similarly to those who invest in works of art, a collector of rare coins can enjoy the spoils of another era whilst experiencing a tremendous upside in resale potential. Tales of wild growth in collectibles have definitely increased investor interest in collecting rare coins.

Guide to Ancient Greek Coins

Weights and Denominations

Below are the weights of Ancient Greek coins:

- Attic standard: derived from the Athenian, 4.3-gram silver drachma

- Corinthian: derived from the 8.6-gram silver stater, subsequently divided into three silver 2.9-gram drachma

- Aeginetan stater: 12.2-gram didrachm, derived from 6.1 gram drachma

Ancient Greek coins were valued in “drachmae” (meaning “handful”) and “obols” (meaning “spit” or “rotisserie”). Six obols are worth one drachma. Below are the denominations of Ancient Greek coins:

- Dekadrachm: were worth 10 drachmae, weighing 43 grams

- Tetradrachm: were worth 4 drachmae, weighing 17.2 grams

- Didrachm: were worth 2 drachmae, weighing 8.6 grams

- Drachma: were worth 6 obols, weighing 4.3 grams

- Tetrobol: were worth 4 obols, weighing 2.85 grams

- Triobol: were worth 3 obols, weighing 2.15 grams

- Diobol: were worth 2 obols, weighing 1.43 grams

The sub-obol coins are named Tritartemorion, Hemiobol, Trimitartemorion, Tetartemorion, and Hemitartemorion, the latter of which weighing just .09 grams.

Archaic Period

At some point before 600 BC, the very first known coins were issued in Lydia and Ionia in Asia Minor by the Lydians, a non-Greek people, using coins perhaps for their own use, or perhaps it was because Greek mercenaries wished to be remunerated in precious metals after their service ended. They made these early coins from electrum, which is an alloy of silver and gold prized by the locals and abundant in the region.

By the time of around 550 BC, the coinage methodology had become more advanced and the making of silver and gold coins became somewhat easier. Allowing for gold and silver coins to be forged and then traded in the free market, King Croesus developed the double metal standard of this time.

At a time when the entirety of the Greek world was subdivided into over two thousand self-governing “poleis” or city-states, would you imagine that over half of them struck and traded their own coins? A few of these coins even circulated well beyond their original city-state, and an early example shows the Aegenetan didrachm being found in Egypt and the Levant.

Once these coins were circulated more widely, the Aegenetan standard was born. The Attic standard was common for Athenian coins, where a drachm was equal to about 4.3 grams of silver. The bountiful silver supply at the Laurion mines was used in this period to make the ancient Greek coins of the Attic standard.

Classical Period

Ancient Greek coins arrived at an elevated level of technicality and aesthetic quality during the classical period. Some of the bigger city-states were striking expanded lines of gold and silver coins, the majority of them embellished with their patron goddess or god on the obverse side and some particular emblem of the city on the reverse. We also see an increased use of inscriptions during this period and in rare cases, visual puns and inside jokes, as is the case of the “rose” struck onto the coins of Rhodes, the Greek word for which is “rhodon”.

While Sicilian cities struck many particularly excellent specimens, the 10-drachm silver decadrachm from Syracuse is thought by collectors as the best coin made in the ancient world, and it may be the finest coin of all time. The tyrannical leaders of Syracuse were unimaginably wealthy, and Syracuse was the center of great numismatic creativity during this classical period. Renowned Syracuse engravers Euainetos and Kimon forged coinage of the highest quality in all antiquity.

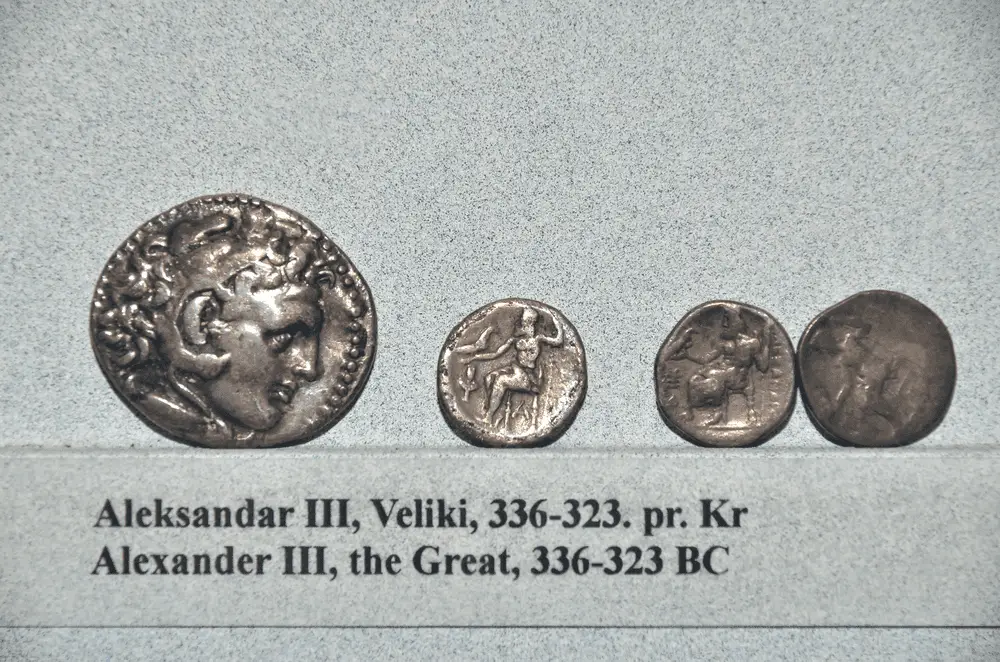

Hellenistic Period

Coins of this era are indicative of Greek culture expanding over a larger area of the known world. There were Greek-speaking kingdoms in both Egypt and Syria, and even Iran, Afghanistan, and northwestern India were touched by the Greek diaspora. This, of course, meant that not only were traders disseminating existing Greek coins across this massive area, but the newer kingdoms were striking their own coinage. Here we find more gold coins produced on a larger scale than was previously known.

This period would oversee the production of the largest silver coin ever minted, struck by Eucratides around the 2nd century BC. The practice of using depictions of living rulers was becoming more prevalent in the Hellenistic Period. This was originally a Sicilian idea rebuffed by Greeks at first, but henceforth accepted by Ptolemaic and Syrian kings as well. The profile of a living king on one side of a coin and his coat of arms on the other became common.

Symbols of the City-State

Known as a badge or emblem in numismatics, ancient Greek coins developed the use of a unique logo or feature relating to their particular city-state or “polis”. These coins were meant to show off the prestige of a certain city-state. The sacred bee of Artemis was featured on the coinage in Ephesus, for example, while in Bela, coins were struck with a man-headed bull, in Athens the owl of Athena, and in Heraclea, we find an image of Hercules. One very famous and sought after coin is one that was produced in Knossos bearing a labyrinth and the great mythical Minotaur.

Final Words

Collectors and investors count on rare coins to represent an investment horizon on par with their other investments and one lasting from several months to a few years. Some instances of coins being turned around in a matter of months for profit are not unheard of, but in general, an investment in rare coins is a patient game. A good rule to live by is conducting thorough research and ensuring that at a minimum you will see a return equal to your investment.

Those who are obsessed with owning tangible items of ancient history are the usual collectors of and investors in rare coins. Known as the “king of hobbies” coin collecting is accessible to anyone, however, as it is a little-known fact that there is somewhat of an abundance of ancient Greek coins in the world. But similar to finding a Honus Wagner baseball card or a ceramic Meiji dish, collectors of ancient Greek coins are always on the lookout for the rarities, such as a Julius Caesar or Alexander the Great.